During my coaching session with Alexander, a talented scientist and emerging leader at a biotech firm, I observed a familiar struggle that often arises in countless mentoring relationships. As we discussed her challenges with a team member who consistently underperformed despite her patient guidance, I asked what seemed like a straightforward question: "What motivates you, Alexander?"

The silence that followed was telling. Here was someone articulate, passionate, and deeply engaged in her work, yet she struggled to answer this fundamental question about herself. "I could probably give five different answers," she finally admitted, "because there are so many different things."

This moment crystallized something I've observed throughout decades of mentoring: the most profound and often most difficult question we can ask—or be asked—is, "What do you want?"

The Deceptive Simplicity of a Complex Question

On the surface, "What do you want?" appears elementary. Yet, in all my years of mentoring and coaching, I've found it to be the question that generates the most extended pauses, the most uncertain responses, and often the most significant breakthroughs. The difficulty isn't intellectual—it's deeply human, rooted in five fundamental challenges that make this simple question so complex to answer.

First, we don't know what we don't know. Life experience provides the context for understanding possibilities, but early in our journey, we lack the exposure necessary to envision what we might truly desire. Sarah, in her college uncertainty, couldn't articulate what she wanted beyond the vague notion of "success" because she hadn't yet encountered the breadth of possibilities that lay before her. Our inexperience limits the menu of options available to choose from.

Second, analysis paralysis weighs heavily on perfectionist tendencies. When we do begin to see possibilities, the sheer number of options can become overwhelming. We get caught in endless cycles of weighing pros and cons, seeking the "perfect" choice rather than a good choice that can be adjusted along the way. The fear of making the "wrong" decision keeps us frozen in indecision.

Third, we're often more concerned with everyone else's wants and needs than our own. This tendency toward external focus, while admirable in its concern for others, can leave us disconnected from our desires and aspirations. We become so adept at reading and responding to others' needs that we lose touch with our internal compass.

Fourth, we often make choices that are designed to make others happy rather than pursuing our authentic desires. The people-pleasing tendency runs deep in many of us, leading to decisions based on what we think others want us to want rather than what genuinely resonates with our hearts and minds. We choose paths that garner approval rather than fulfillment.

Finally, our mixed motives complicate every decision. We struggle with questions of right versus wrong, good versus bad, and the efficacy of our choices. The complexity of human motivation means we rarely have pure motives for anything, and this ambiguity can paralyze us when trying to articulate what we truly want.

The Breakthrough with Alexander

My conversation with Alexander effectively illustrated these challenges. When I asked about motivation, she immediately recognized the difficulty. "Even if somebody asks me what motivates you, I will have difficulty answering that question," she confessed. "It's like a lot of things."

But then I shifted the approach, drawing from techniques I've learned to work more effectively: "What if instead of asking what motivates you, I asked about your favorite part of the day when you come to work? What brings you the most satisfaction? What gives you a sense of joy?"

The change was immediate. "I will know what's my favorite part of the day," she responded with sudden clarity. "It's easier."

This breakthrough moment demonstrated a crucial principle: the path to understanding what we want often requires approaching the question from multiple angles rather than confronting it head-on. Just as Alexander discovered she could identify specific moments of satisfaction more easily than abstract motivations, mentees often need help unpacking their desires through concrete, experiential questions rather than philosophical ones.

The Three Pillars of Getting Specific

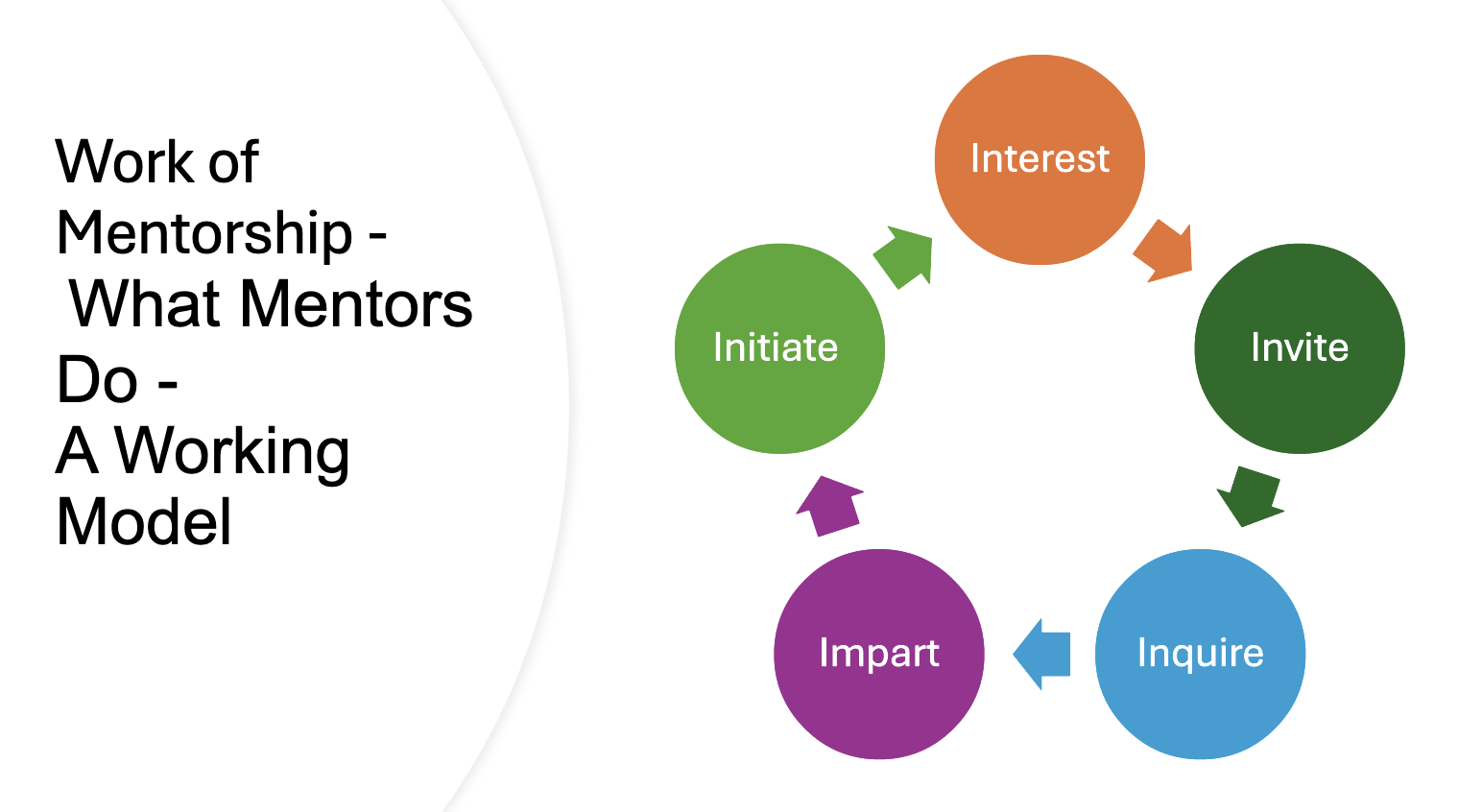

Successful mentorship moves beyond general encouragement and empathetic listening—though both have their place—toward specific, targeted development in three key areas: interests, desires, and growth opportunities. These three pillars provide structure for the kind of deep, transformative mentoring that creates lasting change.

What Interests You?

Understanding interests goes far deeper than identifying hobbies or casual preferences. True interests represent those areas where natural curiosity, energy, and engagement converge. They're the topics, activities, and challenges that capture attention not because they're required but because they're compelling.

In my session with Alexander, I learned about her passion for investments, her interest in interior design, and her desire to study law someday. These weren't disconnected pursuits but windows into her authentic self—someone who thinks strategically, appreciates design and systems and is drawn to advocacy and justice. Understanding these interests provided crucial insight into what energizes her and how she might channel that energy in her leadership role.

The challenge for mentors is helping mentees recognize and articulate these interests when they've become buried under expectations, responsibilities, and the daily grind of life. Questions that help uncover genuine interests include:

What topics do you find yourself reading about in your free time?

When you're in a bookstore or scrolling online, what catches your attention?

What conversations energize you rather than drain you?

What activities make you lose track of time?

What problems do you find yourself wanting to solve, even when it's not your job?

These interests become the foundation for understanding what someone truly wants because they reveal what naturally draws their attention and energy.

What Are Your Dreams and Desires?

Moving from interests to desires requires courage—both from mentee and mentor. Desires often feel more vulnerable to share because they reveal our hopes, our ambitions, and our longings. They're the "what if" scenarios that we may not have shared with anyone else.

Alexander's example with her challenging team member revealed something important about mentoring relationships: when someone can't articulate what they want, it becomes challenging to provide meaningful guidance. "I don't have a lot to work with," she admitted about her team member, echoing what many mentors feel when mentees remain vague about their aspirations.

Dreams and desires aren't always grand or dramatic. Sometimes, they're straightforward: the desire to feel confident in difficult conversations, to find work that feels meaningful, to have better relationships with family members, or to develop a skill that's always seemed appealing. The key is creating space for these desires to be expressed without judgment or immediate problem-solving.

The mentor's role is to help mentees feel safe enough to voice these desires and then take them seriously. This means:

Listening without immediately offering solutions

Asking follow-up questions that help the mentee explore the desire more deeply

Validating the importance of the desire rather than dismissing it as impractical

Helping connect desires to concrete possibilities and next steps

How Do You Want to Grow and Develop?

The third pillar addresses growth and development, which requires an honest assessment of current reality alongside a vision for future possibilities. This is where mentoring becomes most practical and actionable because growth can be measured, progress can be tracked, and success can be celebrated.

Alexander's self-awareness about her need to become more assertive and clear in her leadership style exemplified this kind of growth-focused thinking. She could identify specific areas where she wanted to develop: "I want to learn to be more assertive, I want to be clearer, and I want to understand my people and what motivates them."

This specificity transformed our mentoring relationship from general encouragement to targeted development. We could create action steps, practice scenarios, and measure progress in ways that would have been impossible with vague goals like "becoming a better leader."

Growth-oriented questions help mentees identify specific areas for development:

What skills would you like to have that you don't currently possess?

What aspects of your current role or relationships would you like to improve?

What feedback have you received that you'd like to address?

Where do you feel stuck or frustrated in your current development?

What would you need to learn or change to reach your desired future?

The Power of Specific Partnership

When mentees can articulate what interests them, what they desire, and how they want to grow, mentorship transforms from casual coffee meetings into focused partnerships directed toward meaningful goals. This specificity creates several powerful dynamics:

Traction builds focus. Clear objectives create momentum. Instead of wandering through general life discussions, conversations become purposeful and directed. Both mentor and mentee know what they're working toward, making every interaction more valuable.

Progress becomes measurable. Specific goals allow for particular measurements. Alexander could track her progress in having assertive conversations, understanding her team members' motivations, and clarifying her leadership style. This measurability makes progress visible and creates motivation for continued growth.

Celebrations become meaningful. When goals are specific, achievements can be celebrated appropriately. Success isn't vague or subjective—it's concrete and recognizable. These celebrations strengthen the mentoring relationship and motivate continued growth.

Accountability becomes natural. Clear expectations create natural accountability. When both parties understand what the mentee is working toward, follow-up conversations naturally focus on progress, challenges, and next steps.

The Foundation for Lasting Impact

Getting specific about interests, desires, and growth creates the foundation for mentoring relationships that produce lasting impact. When mentees can clearly articulate what they want, mentors can provide targeted guidance, relevant resources, and appropriate challenges. The relationship evolves into a true partnership, focused on specific outcomes, where shared goals foster a deeper connection and achieved outcomes lead to lasting satisfaction for both parties.

The question "What do you want?" may never become easy to answer, but it remains the gateway to mentoring relationships that truly transform lives. Being specific serves as a powerful indicator of priorities, passions, and pain points, allowing for an authentic partnership. Yet, knowing what you want may be the gateway to more profound clarity about your values, beliefs, and purpose.

Master mentors have the patience to delve into the depths of these conversations, moving beyond surface desires to uncover what truly matters beyond the trivial. As you engage in these deeper conversations, you may discover areas that stretch beyond your scope of expertise. These moments reveal when we need to know our grace—when to engage fully and when to refer wisely.